May contain lies

Alex Edmans is Professor of Finance at London Business School. This article is taken from his book ‘May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases – And What We Can Do About It’ which was published by Penguin Random House on 25 April 2024.

In an extract from his recent book, Alex Edmans explains why misinformation affects us all and how our intrinsic biases impact on our understanding.

The sweat was dripping down my face as I awaited my grilling in the UK House of Commons. I’d been summoned to testify in front of the Select Committee on Business. This was a group of MPs who, infuriated by a couple of high-profile scandals, had launched an inquiry into corporate governance.

In my day job as a finance professor, I’m used to being interrogated by students in lectures, journalists in interviews, and executives in workshops. But being probed by MPs on live TV and having your testimony transcribed as public record is another level, so I was feeling pretty nervous. I got to the House of Commons early and sat in the session before me, burying my head in my notes to swot up on every question the Committee might ask.

My ears pricked up when a witness in that session mentioned some research that sounded noteworthy. It apparently found that companies are more successful when there’s a smaller gap between the pay of the CEO and the pay of the average worker. I was intrigued, because my own research shows that employee-friendly firms outperform their peers. My studies don’t focus on pay, but this new evidence appeared to complement my findings. For many years I’d been trying to convince companies about the importance of treating workers fairly, and this looked like another arrow to add to my quiver. I wanted it to be true.

If my 20 years in research has taught me anything, however, it’s to not accept claims at face value. I pulled up the witness’ written statement and saw they were referring to a report by Faleye, Reis, and Venkateswaran. But when I looked it up, it seemed to say the exact opposite: the higher the gap between CEO and worker salaries, the better the company performance.

I was confused. Perhaps my nerves meant I’d misunderstood the study? After all, academic papers aren’t known for their lucidity. Yet their conclusion was right there on the front page and as clear as day: companies do better if they have greater pay gaps.

It then dawned on me what had happened. The witness statement actually quoted a half-finished draft by Faleye, Reis, and Venkateswaran that was three years out of date. I was looking at the published version, after it had gone through peer review and corrected its mistakes – leading to a completely opposite result.

The witness in question was from the Trades Union Congress, which has a strong public position against pay gaps. In 2014, they published a report declaring that ‘high pay differentials damage employee morale, are detrimental to firm performance [and] contribute to inequality across the economy’. So they may have jumped on this preliminary draft, without checking whether a completed version was available, because it showed exactly what they wanted.

In the corridor afterwards, I told the Clerk to the Select Committee about the tainted evidence. He seemed appalled and asked me to submit a formal memo highlighting the error. I did so, and the Committee published it. Yet the Committee’s final report on the inquiry referred to the overturned study as if it were gospel. It wrote ‘The TUC states that “There is clear academic evidence that high wage disparities within companies harm productivity and company performance’’’ – even though the TUC’s statement was contradicted by the very researchers they quoted. Partly due to this claim, the report recommended that every large UK company disclose its pay gap, and this eventually became law.

The takeaway I’d like to draw is nothing to do with pay gaps – whether they should be published, or whether large gaps are good or bad. Instead, it’s to stress how careful we need to be with evidence.

This episode taught me two lessons. First, you can rustle up a report to support almost any opinion you want, even if it’s deeply flawed and has subsequently been debunked. A topical issue attracts dozens of studies, so you can take your pick. Phrases like ‘research shows …’, ‘a study finds …’, or ‘there is clear academic evidence that …’ are commonly bandied around as proof, but they’re often meaningless.

Secondly, sources we consider reliable, such as a government report, may still be untrustworthy. Any report – by policymakers, consultancies, and even academics like me – is written by humans, and humans have their biases. The Committee may have already felt that pay was too high and needed to be reined in, which is why they launched the inquiry to begin with.

Importantly, we’re all affected by research even if we never read a single academic paper. Each time we pick up a selfhelp book, browse through the latest Men’s Fitness, Women’s Health or Runner’s World, or open an article shared on LinkedIn, we’re reading about research. Whenever we listen to an expert’s opinion on whether to invest in crypto, how to teach our kids to read, or why inflation is so high, we’re hearing about research. And information is far broader than research – our news feeds are bombarded not only with ‘New study finds that …’ but also anecdotes like ‘How daily journalling boosted my mental health’, hunches such as ‘Five tips to ace your job interview’, and speculation like ‘Why we’ll colonise Mars by 2050.’ Blindly following this advice, you could find yourself sicker, poorer, and unemployed.

You might think that the solution is simple – to check the facts. And this is indeed what people do, but only when it suits them. If I share a study on LinkedIn whose findings people don’t like, there’s no shortage of comments pointing out how it might be flawed – exactly the kind of discerning engagement I’m hoping to prompt. But do I see the same critical thinking when I post a paper that finds their favour? Unfortunately not; they lap it up uncritically.

Why do we leave our wits at the door and rush to accept a statement at face value? Sun Tzu’s The Art of War stresses how you should ‘know your enemy’ before drawing up battle plans. So in a new book, May Contain Lies: How Stories, Studies, and Statistics Exploit Our Biases – and What We Can Do About It I start in Part I (‘The Biases’) by learning about our enemy. It takes a deep dive into the two psychological biases that are the two biggest culprits in causing us to misinterpret information.

The first is confirmation bias. We accept evidence uncritically if it confirms what we’d like to be true, and reject ‘inconvenient truths’ out of hand because we don’t want to believe them. Confirmation bias is particularly problematic for topics such as politics, religion, and climate change, where people have strong existing views. But for many day-to-day decisions, we don’t have a prior opinion.

That’s where the second bias comes in – black-and-white thinking. We’re wired to think that something is always good or always bad, when reality is often shades of grey. Most people think ‘protein’ is good. You learn in primary school that it builds muscle, repairs cells and strengthens bones. ‘Fat’ just sounds bad – surely it’s called that because it makes you fat? But ‘carbs’ aren’t so clear-cut. The Atkins diet went viral because it preyed on black-and-white thinking, telling people to minimise carbs. That’s far easier to follow than advising them to ensure carbs are 45‒65% of their daily calories, which would force them to calorie-count. If Atkins’ diet had recommended eating as many carbs as possible, it might still have spread like wildfire as that too would have been easy. To pen a bestseller, Atkins didn’t need to be right. He just needed to be extreme.

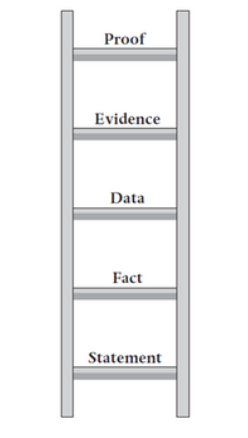

Part II (‘The Problems’) studies the consequences of these biases. They lead us to climb the Ladder of Misinference shown below:

We accept a statement as fact, even if it’s not accurate – the information behind it may be unreliable, and may even be misquoted in the first place. We accept a fact as data, even if it’s not representative but a hand-picked example – an exception that doesn’t prove the rule. We accept data as evidence, even if it’s not conclusive and many other interpretations exist. We accept evidence as proof, even if it’s not universal and doesn’t apply in other settings.

Importantly, checking the facts only saves us from the first mis-step up the ladder. Even if the facts are correct, we may interpret them erroneously, by over-extrapolating from a single anecdote or ignoring alternative explanations. The word ‘lie’ is typically reserved for an outright falsehood made deliberately, and to accuse someone of lying or calling them a liar is a big step. But we need to take a broader view of what a lie can involve, so that we can guard against its many manifestations.

‘Lie’ is simply the opposite of ‘truth’. Someone can lie to us by hiding contradictory information, not gathering it in the first place, or drawing invalid conclusions from valid data. The Select Committee’s claim that ‘The TUC states that …’ is strictly correct – but it’s still a lie as it suggests the TUC’s statement was true when the Committee knew it had been debunked. Lies also have many causes – some are wilful and self-interested; others are a careless or accidental result of someone’s biases; and yet more arise from well-intentioned but excessive enthusiasm to further a cause they deem worthy.

This wider definition of ‘lie’ highlights how regulation can’t save us from being deceived – it can only make someone state the facts truthfully; it can’t stop him claiming invalid implications from them. It’s up to us to protect ourselves. Even if a report has been signed off by the government, a paper has been published by a scientific journal, or a book has been endorsed by a Nobel Laureate, they should all carry the same health warning: ‘May contain lies’.

To distinguish between truth and lies, and gain a deeper and richer understanding of the world around us, we need to do more than just interpret statements, facts, data, and evidence correctly. Part III (‘The Solutions’) goes beyond the ladder. It moves past evaluating single studies to learning scientific consensus, and assessing other sources of information such as books, newspaper articles, and even our friends and colleagues. From learning how to think critically as individuals, we then progress to exploring how we can create smart-thinking organisations, that harness our colleagues' diversity of thought, overcome groupthink, and embrace challenge.

Now more than ever, we have easy access to scientific research by the world’s leading minds, yet it’s drowned out by fallacies, fabrications and falsehoods. Knowing what to trust and what to doubt will help us make shrewder decisions, comprehend better how the world works, and spread knowledge rather than unwittingly sharing misinformation. This in turn allows us and our families to lead healthy and fulfilling lives, the businesses we work for and invest in to solve the world’s biggest problems in profitable ways, and the nations we’re citizens of to prosper and thrive. By recognising our own biases, we can view a contrary perspective as something to learn from rather than fight, build bridges across ideological divides to find common ground, and evolve from simplistic thinking to seeing the world in all its magnificence.